British fight with V-1 and V-2

While British public opinion was impatiently expecting the imminent end of World War II as a result of the opening of the Western European front, Great Britain was suddenly subjected to a massive attack using new weapons: V-1 flying bombs and V-2 ballistic missiles. British planners began a difficult fight against a previously unknown threat.

Despite air raids on numerous targets in Western Europe from mid-1943, British planners suspected that it was only a matter of time before the Germans adopted new, hitherto unknown weapons. As early as November 1943, the Ministry of Aviation was given responsibility for preparing reports on long-range missiles, air defense plans, and coordinating defense and intelligence work. Air Marshal Roderick M. Hill took charge of the British Air Defense (ADGB). He was ordered to analyze the available forces and means to protect against threats, which, however, was difficult, since the technical parameters of the new threat were not known. This is best evidenced by the lack of confidence in the actual performance of the B-1, which was estimated to have a flight altitude of 150 to 2100 m and a speed of 400 to 670 km/h. Even less was known about V-2 ballistic missiles. Some British scientists doubted that such missiles even existed.

By December it was decided that the defense of Britain should be based not only on offensive measures (constant bombardment), but also on defensive measures such as anti-aircraft batteries, air barrages and interceptors. They were supposed to create three lines of defense against missiles approaching British cities, primarily London. Closest to the coast were to be interceptors, performing patrol flights throughout the day. Aircraft for anti-missile operations and soon after the launch were planned to be transferred at night. All available anti-aircraft guns were planned to be placed in the North Downs Hills in the south-east of England - about 500 heavy and 700 light.

In 1943, on the northern coast of France, the Germans began building V-1 rocket-carrying aircraft (colloquially, flying bombs) and shelters for their storage.

Hill spent the second half of December 1943 finalizing the plan. He was convinced that, regardless of the scale and form of the attack, Britain had limited air defenses. New technologies such as electromagnetic interference were considered too energy intensive and were abandoned over time. However, the use of unguided anti-aircraft missiles, which were already in use by that time, was not taken into account, because a very large number of them would have to be directed towards the target. There was no other way out but to rely on proven methods - at least to learn about the key aspects of creating various defenses (nature of weapons, technical data, forms and scales of attack, direction of attack) - on proven methods. Already on January 2, 1944, less than a month after receiving the order, Hill presented a ready-made plan for deploying air defense systems in London, Bristol and the Solent region. It was assumed that the unmanned aerial vehicle would move at a speed of about 650 km / h at an altitude of 2200 m. The defense was based on the use of radar and ground observers to detect incoming missiles. Interceptor aircraft were of key importance, after the warning signal they were supposed to start patrolling the south coast in the area between South Foreland and Beachy Head at an altitude of 3600 m. Anti-aircraft batteries were also allocated. The project called for the deployment of 1800 heavy and 400 light anti-aircraft guns and 346 searchlights to aid detection and tracking in the southern suburbs of London. Because of the fear of launchers in the Cherbourg area, it was planned to prepare a ground defense in the Bristol area, consisting of 216 heavy and 32 light guns. On the Cobham-Kent-Limpsfield-Surrey line, it was planned to create a barrier consisting of 242 barrier balloons. Each formation had to act in such a way as not to interfere with others.

The air dam was planned to stretch between Caterham in the west and Cobham in the east (their number quickly increased to 1,4). Batteries for the defense of the capital were to be deployed in the area of the North Downs, and batteries for the defense of Bristol - in the area of Yeovil-Shaftesbury. Various scenarios were also created regarding the number of anti-aircraft guns required, which mainly depended on the needs of Operation Overlord. Eight day squadrons were to be allocated and eight squadrons were to be assigned to night flights. Developed in February 1944, the plan was approved over the next few days by Air Marshal Leigh Mallory, General Eisenhower, RAF High Command, and finally by Prime Minister Churchill. After the implementation of the truncated plan, the British had to wait for an air attack and continue to deliver air strikes.

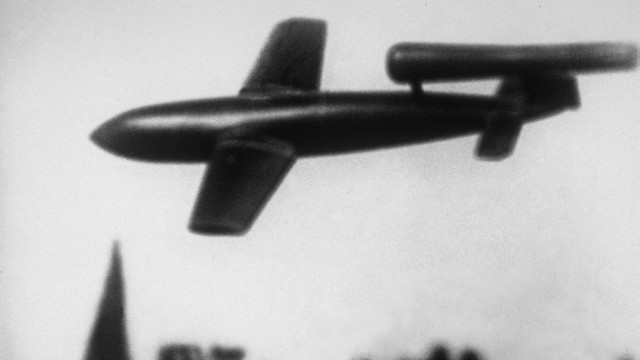

The V-1 was equipped with an Argus As 014 impulse jet engine, it could reach speeds of 645 km / h and had a flight range of 240 km (take-off weight 2150 kg, including a destructive combat load of 850 kg).

Diver, Diver, Diver!

If some experts still doubted the existence of a new and revolutionary weapon, then an unusual explosion on the morning of June 13, 1944 left no illusions. Three months after London's scheduled date for the attack on Britain, the first German rocket fell. Others followed. The Allied Air Force immediately bombed targets at Beauvoir and Domlèges in northern France. Public opinion remained indifferent, as no one realized that this was an attack by a new German secret weapon. However, among the high command there was a commotion - disappointment mixed with surprise and amazement. Some people were visibly disappointed with the poor effect of the bombings of Operation Crossbow. The V-1 strike meant that the German factories could not be torpedoed. All those who predicted the German air offensive were positively surprised by the relatively small amount of damage inflicted. The attack was expected to start with at least 400 tons of explosives in the first 10 hours. For this reason, the number of planned bombing attacks on launchers has been reduced from 3 to XNUMX. There were even voices in the high command that this modest German attack was intended only to distract the Allies and slow down the operation on the Western Front.

Due to the low accuracy, the V-1 missile carrier was suitable only for strikes against large-area targets, such as cities (software, gyroscopic guidance).

The number of V-1 attacks grew rapidly. In just a dozen or so minutes on the night of June 15, 151 of over 200 rockets fired crossed the UK border. 73 reached London: 14,5 of them were shot down by anti-aircraft artillery fire, another 7,5 were shot down by fighters. Dozens of bombs were fired towards Southampton. No one could say with certainty whether the strike was the beginning or end of the air campaign. It is also not known at what stage the production of ballistic missiles is. However, the scale of the impact was so great that it was decided to carry out specific political and military actions. A day later, Minister Herbert Morrison acknowledged in Parliament that Britain had been attacked by "flying torpedoes". At the same time, the members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff concluded that the deployment of the defense components envisaged for Operation Diver should begin as soon as possible. Searchlights were in place, balloons were to be released within 48 hours. The deployment of anti-aircraft batteries proved more problematic, as some of them were assigned to Operation Overlord.

On the same day, Prime Minister Churchill convened a meeting at which key decisions were made. The head of government made no secret of the fact that he was ready to use chemical weapons if the bombing of London became a serious inconvenience and German missiles fell on government and workers' quarters. I am ready to do everything to inflict a mortal blow on Germany. I would like you to support my proposal for the use of poisonous gases. We could offer them to the cities of the Ruhr and other cities in Germany, so that most of the inhabitants would need constant medical care. We could stop all work on launchers for V-1 missiles. As he himself added, it will be several weeks or even months before I ask you to attack the Germans with poison gas. In the meantime, I want the case to be investigated calmly. As he himself stated, the blind, impersonal nature of flying rockets made people feel powerless. There were ideas to attack small German cities in response instead of large urban centers, recognizing that the complete destruction of a small population center would have a much greater psychological effect. Dwight Eisenhower, against the suggestions of some of his generals such as the still skeptical Spaatz or Doolittle, withdrew 40 percent of all RAF and USAAF vehicles from bombing German factories and installations, diverting them to the Crossbow mission.

On 17 June, a hospital in Kensington was hit by a flying bomb, killing 18 people, mostly children. By June 18, the Germans had already fired 500 flying bombs. One of them crashed directly into the chapel of Wellington Palace, less than 300 meters from Buckingham Palace. The explosion killed 58 civilians and 63 military personnel. On the same day, the V-1 damaged 11 factories, and Churchill ordered the evacuation of Parliament to begin. By June 27, 1944, 1769 people had died from flying bombs, and by July 5, this number had increased to 2,5 people. Shelters in which more people now sought respite and safety than during the memorable Blitz in the summer of 1940. Staff meetings with Churchill were transferred to underground bunkers. Despite further air raids, by mid-July 1944, 4 rockets were fired at London, 3 of which flew near the capital, which the British again hastily left.

It was a huge blow to British morale. Soon after the largest amphibious operation in history began, victory was expected soon, and not a return of the horror and uncertainty of tomorrow in 1940. Instead of the desired success at the front, the people of Great Britain had to hide again in shelters. Sensations and rumors multiplied - it was whispered in disbelief that the V-1 bombs had extraordinary, supernatural abilities, were able to choose a target and chase their victim through the streets. Some have seen the ghosts of the victims roam the ruins of the destroyed houses at night. Others spoke of German spies prowling the streets in the evenings to select targets to attack. Over time, even the Spanish regime of Francisco Franco was accused of building V-1 fragments in Pamplona and Madrid. Sentiment continued to worsen despite the introduction of strict censorship, which forbids the media from talking about the real consequences of the V-1 and the victims.

The first attack by V-1 launch vehicles was delivered on the night of June 13-14, 1944, firing ten V-1s towards London, of which only four reached the British Isles.

Effective air defense required, above all, a clear coordination of the efforts of all formations. Practice has shown that the fight against unmanned aerial vehicles is a big organizational and technical challenge. It was necessary to make the most of the available forces and means and to unite the command. In other words, to make all air defense components work smoothly, and not interfere with each other. The flow of information left much to be desired - for example, when the decision was made to redeploy light artillery, it turned out that the Royal Air Force had deployed an additional air barrage at the destination. The second fundamental problem was the interaction of interceptor pilots and anti-aircraft batteries. The pilots often entered the artillery coverage area, which caused damage to the vehicles and made it difficult for the artillery to work. As a result, on June 19, the pilots were forbidden to enter the artillery fire zone - except in cases of direct and continuous pursuit. However, there were still dangerous moments when the pilots violated their zone of action, flying directly under artillery fire. Problems with the coordination of air defense actions led to the fact that Marshal Hill himself sat at the controls of the fighter, performing tasks against the V-1, which made a total of 62 flights on various machines.

Protection concept

In total, the Air Command launched about 2 balloons into the sky. The return to somewhat archaic methods is due to the fact that if for manned aircraft evading the dam is not a problem (at best, this can lead to a loss of battle formation, which makes it difficult to conduct an organized and therefore effective bombing strike). ), for flying bombs, it could be an insurmountable obstacle. The effectiveness of balloons was negligible, so they were treated as the last element of defense. The Polish pilot Bogdan Arkt, flying to the UK, describes their usefulness in this way: The balloon dam, although it consisted of more than two thousand balloons, did not fulfill its task, and the V-1 passed through it like a sieve, and sometimes only, very rarely , after the meeting, they twisted in flight on a steel cable, lost their balance and fell to the ground like an ordinary plane, only to immediately shatter into smithereens with a powerful explosion.

Traditional anti-aircraft artillery to intercept Luftwaffe aircraft was at the center of the defense system. Great Britain used at that time mainly two types of guns - heavy "Vickers" caliber 94 mm and Swedish "Bofors" caliber 40 mm. Others, such as the 20 mm caliber, were of lesser importance due to the ceiling being too high for the flying bombs to work. Often, even in the event of a hit, a projectile of such a small caliber was not able to penetrate the armor of the V-1. Especially the first guns, put into service in 1937, were highly efficient, reaching 82 percent. The British defense was supported by the Americans, equipped with 268-mm radar-guided M584 anti-aircraft guns (SCR-1, then SCR-90). After dark, the batteries maintained powerful headlights that illuminated the sky, making it easier to track an object and fire.

Of course, it wasn't without problems. It is true that the V-1 bomb seemed like a good target due to its stable trajectory, but it was still a fairly small object, making effective fire difficult. The short reaction time was also important - up to 20 minutes from the moment the launcher left. It was easier to hit one of the many bombers than one tiny dot in the sky. Even worse, the V-1 was capable of operating in difficult weather conditions (even in strong winds, although the wind changed the flight path), which distinguished it from aircraft that had to be limited in good weather. Moreover, there was no fixed ceiling and no constant speed - which meant that each unmanned missile had to be considered individually. Most of the bombs operated at altitudes from 350 to 1200 m. Their speed ranged from 400 to 650 km/h.

The fight against the V-1 consisted of destroying missile launchers, shooting down or throwing them out of action by fighters, shooting down anti-aircraft artillery and using balloon obstacles.

Radar operators faced not only short reaction times, but also difficulties in detecting missiles. Although the radars installed in the late 200s had a claimed range of about 1 km, in practice the detection of the V-80 occurred only 1944 km from the station. The main problem was distinguishing a missile from an aircraft - a difficult task, especially given the heavy air traffic over the English Channel since June 14. Difficulties with identification led to an urgent upgrade of four radar stations: at Beachy Head and Fairlight. (until July 9th) and Swingate and Foreness (until August XNUMXth). Instruments were also tested that were supposed to distinguish between the operation of engines, but they were unsuccessful.

Much more fruitful to the overall effectiveness of British air defense was the use of modern American radio early warning (MEW) systems. The main advantage of the device, which has been in use at Fairlight (East Sussex, east of Hastings) since June 29, was its greater detection range - and therefore more time to take defensive action. As the American-provided system was shipped to France in August, the British stepped up work to complete their own Type 26 radar station. Second in seaside Saint Petersburg. Margaret Bay (Kent, southeast of Canterbury, 111 km east of London). In three places (Beachy Head, Hythe, Fairlight), special cameras were additionally installed, which, by photographing, were supposed to help detect the V-1 rocket launcher.

In most cases, anti-aircraft batteries did not have direct radar support. The American company MIT Radiation Laboratory came to the rescue with its modern microwave radar system SCR-584 (Signal Corp Radio), which made its debut on the Anzio battlefield in February 1944. There was no consensus among British decision makers about the need to invest in a very expensive system, which averaged PLN 100. Despite the insistence of the commanders in charge of British air defense, an order was placed in the United States for 430 sets. Ultimately, 165 of these vehicles were delivered to the UK, to the delight of the planners, who cheered that without this equipment it would be impossible to fight flying bombs.

The SCR-584 replaced the obsolete British Mark II and Mark III radars, as well as the American SCR-268. Together with a special analog computer (M-9 Gun Predictor), the system could efficiently target four 90 mm anti-aircraft guns using an electrical signal. The antenna emitted a short signal, which was analyzed after returning. If the interval between sending and receiving a signal was 100 microseconds, in practice this meant a target distance of 15 km. The maximum interval was 240 microseconds, which meant that tracking could occur at a distance of about 30 km. The object detection zone was much larger, as much as 85 km. There were no blind spots, so any flying projectile - regardless of height - could be detected. The radar also made it possible to determine the speed of an object, its height and flight path. It also had a simple mechanism for recognizing enemies and friends. The complex was able to monitor objects moving at a speed of more than 18 kilometers per hour at an altitude of up to 000 m. After detecting a target, the radar changed its function from detection to tracking, allowing it to open fire, including in poor conditions. weather and at low altitudes. Thus, for the first time in history, one machine successfully fought another machine without human intervention. The work of the crew was reduced only to the loading of ammunition.

About 1600 V-1 rockets were fired by the Germans from bombers. Usually He 111 bombers were used for this purpose (V-1 rockets were launched over the North Sea).

After being detected by radar, the command center sent interceptors to meet the enemy, which were the first line of defense. The radar operator on a permanent basis transmitted to the pilot information about the location of the object (the so-called close control system). Installations in Fairlight, Swingate and Beachy Head were originally used for this task. The main problem was that, due to technical limitations, the radars could not detect an incoming missile at a distance of more than 80 km. At V-1 speed, the rocket reached the coast in just a few minutes. Over land, controllers stationed at Beachy Head, Hythe, Sandwich and the Royal Observation Corps command centers at Horsham and Maidstone provided information to the pilots and they began ongoing commentary at their discretion. Lookouts with flares were also used, which made it possible to identify the bomb, which was difficult to see in the sky. They also relayed valuable information about the missile's engine shutting down, which was a clear sign that the bomb would hit the ground and the chase was unnecessary. Very often, the inhabitants of the disappearing region themselves were looking for threats. The children proved especially helpful in this role.

The first shooting down of a V-1 flying bomb by pilots was recorded on June 16, 1944. It was then that Lieutenant John Musgrave and Sergeant F. W. Somwell in a Mosquito aircraft began a pursuit over the English Channel of a V-1 heading towards London. . After a short chase, a bomb fired from cannons exploded. Many of these successful intercepts were made by Poles who fought in the RAF. One of the stories was included in the book of memoirs of Bogdan Arkt, who described the actions of Lieutenant Longin Mayevsky, commander of squadron "B" of the 316th squadron:

He had a great advantage in speed, so he easily covered the prescribed distance of two hundred meters. He eased the throttle a little so as not to get too close, moved a little to the side and positioned himself to shoot with a slight adjustment in his scope. He measured calmly, coolly. Having fired the first short burst of missiles, he immediately noticed that they were entering the target. He pulled the trigger of the deck weapon a second time. The speed of the bomb suddenly decreased, sparks fell from the mouth of its engine (...) The bomb tightened the turn, dived sharper and sharper (...) At an altitude of five hundred meters, the V-1 turned into a perpendicular dive. A moment, and he hit the surface of the sea. A flash, and with it a mighty column of foaming water splashing in a wide fan. Yes, it was over.

The last line of defense against the attacks of the German V-1 missile carriers in the British air defense system was air barriers.

Carrying out the pursuit and interception procedure was not always easy. The mere appearance of a rocket, even in good weather, could be a problem. Paradoxically, the V-1 was easier to spot at night. The biggest problem for the pilots was the high speed of the V-1, reaching even 630-700 km / h (depending on the wind and the flight stage). For this reason, the aircraft intended for Operation Diver were specially modified for this occasion - unnecessary armor plates were removed, fuel reserves were reduced, engine power was increased, and even the paint was removed from the wings and fuselage, all surfaces were polished. Better quality high octane fuel was used. As a result of the application of these simple techniques, the speed of the cars was increased by 15-50 km / h. To fight a jet enemy, the British mainly used aircraft: Spitfire IX / XII / XIV, Mosquito or P-47 Thunderbolt. P-51 Mustang III was sent to the defense. The Tempest V (695 km/h) showed itself best of all with excellent performance at low altitudes and strong armament. Several Meteor jets were also used.

The high speed of the intercepted object and the narrow band of action of the fighters forced the pilots to develop special tactics. One way was to send the plane on a collision course with the bomb and try to bring it down. This created a lot of problems, the biggest of which was the short response time. The V-1 armor was so thick that many shells could not penetrate it (especially from a long distance). In the event of a miss, the pilot had practically no chance of catching up with the bomb and making another attempt. Over time, pilots developed ways to increase altitude, allowing them to attack from a dive and gain a speed advantage. Many pilots used a more original method - the car, using its speed, approached the side of the V-1 and undermined the wing of the bomb with its wing, causing problems with its gyroscopes and loss of stability (this is only in relation to those that flew quite slowly). The bomb then "attacked" fell to the ground, although the pilot risked damaging the wing. Over time, bored pilots tried to detonate the bomb so that it flew towards France. However, this was a risky move, as the interceptor's fragile wing structure was sometimes damaged when attempting to detonate the steel bomb. According to the British press, this method was discovered by a Polish pilot.

Interestingly, a drop in morale and concentration among the pilots was quickly noticed. The pilots missed the battle with a live enemy and plunged into a routine. He wrote about this in his memoirs Roderick Hill:

It turned out that although some pilots willingly took on the task of shooting down flying bombs, most preferred to shoot down enemy aircraft over France. So not the least of my problems was getting excited about this new fight and drone shooting. Also, pilots were not left at work for a long time so that they would not be blunted.

and they have not lost their sensitivity.

Correction of the assumptions of the protection system

Before the decision was made to strengthen the defense belt quantitatively, on June 16, 1944, the British made adjustments to the rules for deployment and operation. Marshal Hill gave the order to divide the fighter zone. Twelve special fighter squadrons were to operate on three lines: the first in the English Channel from Beachy Head to Dover, the second on the coast from Newhaven to Dover, and the third inland between Haywards Heath and Ashford. Aircraft could enter the artillery coverage area only in the case of continuous pursuit of the missile. Two days later, a decision was made to cease fire with anti-aircraft batteries in the suburbs of London, which caused some discontent among the city's population, surprised by this decision. So if the V-1 passed through the area of interceptor aircraft and anti-aircraft batteries, then there was hope that it would fly over the city and fall into an empty field. A day later, another important order was issued: it was agreed that on days of good visibility, interceptors should take responsibility for intercepting German missiles. On cloudy days, anti-aircraft artillery was supposed to operate, and in "mixed" weather, both formations were in the established areas of operation.

In total, in the air defense system of the United Kingdom, the Air Command launched about 2000 balloons into the sky. About 300 V-1 missile carriers became their victims.

Operating rules depending on altitude and weather conditions quickly proved difficult to implement. The pilots repeatedly complained about the "friendly fire" of ground artillery, as they unknowingly violated the boundaries of the zone. The gunners did not remain in debt, complaining that RAF aircraft made their work difficult by flying into their area of \u10b\u1944boperations. Many vehicles returned to base heavily damaged by their own artillery fire. Already on July XNUMX, XNUMX, free operational zones were abandoned, introducing clear boundaries. The pilots were forbidden to enter the area of operation of anti-aircraft batteries, regardless of the weather and pursuit. The gunners had complete freedom of action, and the pilots acted at their own peril and risk - even the appearance of a friendly interceptor made it possible to continue firing from the ground.

Preparing to repel the German "retaliatory" strike, the British increased, in particular, the number

observation posts in the visual detection and warning system.

Only three days later an even more serious decision was made - to relocate the air defense line from the hinterland towards the coast. The plan was to move the belt of anti-aircraft batteries to the coastal zone (Saint Margaret's Bay - Cookmere Haven), while creating gaps in built-up areas near Eastbourne, Hastings, Bexhill, Hythe, Folkenston and Dover, as well as Beachy Head. and Fairlight, where strategically important radars were located. Thus, the operational zone extended about 9 km into the English Channel and about 4,5 km inland of England. At the same time, the number of interceptor squadrons was increased. As a result of the changes and increased use of modern American proximity fuse ammunition, there has been a significant increase in the effectiveness of the fight against the V-1. In the first week of using the radar and new munitions, anti-aircraft batteries destroyed 16 percent of all flying bombs; in the second - as much as 24 percent, in the third - 40 percent, in the fifth - 55 percent, in the sixth - as much as 74 percent.

Anti-aircraft artillery deployed on the coast was the central line of defense against aircraft.

- V-1 missiles. It had mainly heavy (94 mm) and light (40 mm) guns.

The frequency of attacks using V-1 rockets decreased with subsequent bombing attacks and the Allied advance into France. In early September, when only eight bombs reached England, the last launcher in the Pas de Calais region was captured. The press announced the end of the second "Battle of London". Squadron commanders were informed that all air operations inside the Arbalet had ceased. On September 5, word quickly spread of the surrender of Germany and Churchill's associated speech that evening. Victory celebrations have begun. This was not justified as the attacks continued until 29 March 1945.

According to official statistics, from June 12, 1944 to March 29, 1945, 5890 of the 8839 flying bombs fired crossed the British coast, of which 2563 reached London. The British Isles Defense Force destroyed 4262 missiles. In London, 5375 15 people were killed and 258 were injured. In the rest of the British Isles, 462 people died and 1504 were injured.

Attack V-2

It seemed that as the Allies moved into France, the problem of German shelling of British territory would cease to be relevant. In this illusory, as it turned out, most of the operations associated with Operation Crossbow were stopped. The Air Force was ordered to join the effort on the European front. Censorship was relaxed, allowing journalists to write in a limited way about missed missiles. Anti-aircraft batteries and ground observers lowered the level of readiness. Some of the staff went on vacation. It soon became clear that Britain had made a mistake again. The capture of a launcher in France and the bombing only prevented the Germans from continuing their strenuous campaign with flying bombs. London underestimated the determination of the Germans and the range of ballistic missiles, which exceeded 320 km, and not all launchers in this radius were occupied by the Allies. It soon became clear that the mistake was very costly.

The frequency of Faun-1 attacks on the British Isles decreased significantly after the strengthening of missile defense by tactical bomber aircraft and the rapid advance of the Allied offensive in France.

On September 8, 1944, a V-2 rocket launched from The Hague in Holland and aimed at a point a kilometer east of Waterloo Station fell from the sky into the London Borough of Chiswick, killing three and injuring twenty. Losses would probably have been greater if not for the evacuation of part of the population due to fear of attacks by flying bombs. 11 houses were destroyed, 15 more were in need of major repairs. The resulting funnel, which was immediately examined by British and American experts, had an impressive diameter of 10 m. A few moments later, a second rocket exploded in Parndon Wood (Epping, Essex), damaging wooden houses. The missiles were not detected by either radar stations or ground observers. Just a dozen or so seconds after the explosion, the dazed residents heard a powerful thunder that shook the sky like a thunderbolt that signaled that the faster-than-sound rocket had entered the atmosphere. The absence of a distinctive drone was clear evidence that it could not be a V-1 flying bomb. Although British citizens were unaware of it at the time, their country was the victim of a successful strategic missile strike.

For technical reasons (mainly due to the lack of liquid oxygen), the scale of the missile offensive was much smaller than that of the unmanned V-1 rockets. By September 16, only 20 missiles had been dropped on the UK, 10 of which hit the capital. The government did not inform the public - it did not refute and even initiated rumors about alleged explosions of gas installations. All this in order to delay the decision to confirm the missile offensive as much as possible. As advised by the military, the British authorities wanted to wait.

Only later, Winston Churchill spoke in the House of Commons, officially confirming the information about the German missile attack. He also acknowledged that one could neither prevent nor protect against the V-2. This came as a real shock to the British. After all, the lifting of the blackout and the disbanding of the Home Guard were to send a clear signal that Britain was now free from attack. Churchill's statement confirmed the government's failure to create a false sense of security. For only a dozen or so days ago there had been talk of an end to the threat, and now the government had to admit that the war was going on and that civilians would continue to die in London. In the first week of November, 12 V-2 rockets fell on London, in the second - 15, in the third - 27. The black day was November 25, when only one V-2 killed 6 people and wounded 292.

As early as September 9, members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff held a meeting to determine possible measures to protect against missiles. The category of active actions includes radio interference of guidance signals, further strategic bombing and tactical flights: fighter strikes and reconnaissance and combat flights. Other (passive) anti-missile activities included: preparation of the civil defense system (shelters, evacuation, repair of damage) and detection of ballistic missiles (early warning of the civilian population with an indication of the launch site).

The War Cabinet was then asked not to inform the public about the attack and not to impose too strict censorship. This meant that the civilian early warning system should not have been activated. The military warned that there was little that could be done about the matter. It was recognized that the radar and listening system would only warn the public of 1 in 16 attacks in London or 1 in 6 incidents elsewhere in the country. The proposal to send mobile radar and sound equipment to Belgium was met with restraint - the military was of the opinion that before the corresponding equipment could reach the continent, the launchers would be captured by the army. Despite this, reconnaissance aircraft were sent over the Netherlands to detect and disrupt radio signals. The Dutch resistance movement was also activated, which was supposed to immediately transmit information about the missiles. The first information about the location of the launchers appeared three days later.

While the preparation of a passive defense did not pose a serious technical problem (logistically and financially at best), an active defense - especially after a missile launch - was practically impossible. Fighting missiles was completely different from intercepting jet missiles. The V-2 was a much more complex design than the technically simple pulse-powered V-1. After about 60 seconds of flight, the V-2 reached a speed of 1500 m / s. Then the rocket slowed down to about 1100 m/s, reaching a height above the stratosphere (about 85 km above the ground). As the descent phase began, the velocity increased and then decreased again due to re-entry into the atmosphere. The target was hit at a speed of about 800-1000 m / s. In the case of missiles flying at a maximum range of 320 km, the ceiling reached 93 km, and the flight time was only 5,5 minutes.

The first stage of defense was the detection of an approaching threat. The radar stations were connected directly to the response center, which was ordered to immediately inform the headquarters and leadership of all services involved in missile defense. In practice, however, only 6 of the first 20 missiles were detected, which made it theoretically possible to alert the civilian population. Detection was difficult, if only because of the simplicity of the radars of that time, as well as the small effective reflective surface, which for missiles is only 0,25-0,5 square meters. After the start of the V-2 campaign, additional training of operators was begun, teaching them to detect typical missile traces on the radar. Additional mobile radars were deployed in the south of England, creating a dense network of radars.

A special RAF unit, MARU (105 Mobile Air Reporting Unit), was deployed to the continent, which was created in mid-September specifically for this operation. Its task was to detect launched ballistic missiles, collect data at the initial stage of flight (radio intelligence, radar data, audio and visual surveillance) and coordinate the work of elements of a broadly understood missile defense on the continent. Analog computers were used, capable of calculating the flight path, giving a chance to indicate the approximate launch site and the predicted area of \u60b\uXNUMXbthe missile explosion. This made it possible to warn the population of the danger zone approximately XNUMX seconds before the explosion. It was much more important to determine the launch site, as this made it possible to try to bomb the launcher with tactical aircraft. However, since in practice the launchers often changed places, these actions did not bring the expected results.

Back in the summer of 1943, methods for detecting missiles by sound and light signals were prepared. Four units of coastal artillery between Folkestone and Dover were responsible for observing the light signals, while sound signals were carried out by four units from reconnaissance artillery observing the area of Calais-Boulogne and Abbeville-Fécamp. On the coast there is equipment for photographing northern France and observation balloons. It is worth noting that the British managed to fix the trace of condensation of one of the rockets from September 8 and record the sound of both. As a result, analysts determined that the missiles were launched from the Netherlands.

Ground observers, so adept at air defense against the Luftwaffe and V-1, were now completely out of the question. They could not detect a rocket flying in the upper atmosphere. Even the roar of the rocket did not give any chance of a reaction, as it was a sign that she was already far away. Also in the most optimistic scenario - detecting an object immediately after its launch and determining a potential crash site - there was little time. The matter was not further facilitated by the fact that in the summer and autumn of 1944 the airspace was filled with Allied aircraft. The radar operator had to quickly distinguish his aircraft from an approaching intruder (which was often almost impossible due to inaccurate equipment), determine flight paths and notify civil and air defense. He had no more than three or four minutes to give a warning, which in practice meant that the civilian population would still not have time to escape to shelters. Even there, no one was safe, as the V-2 easily pierced the thick ceilings of the bunkers.

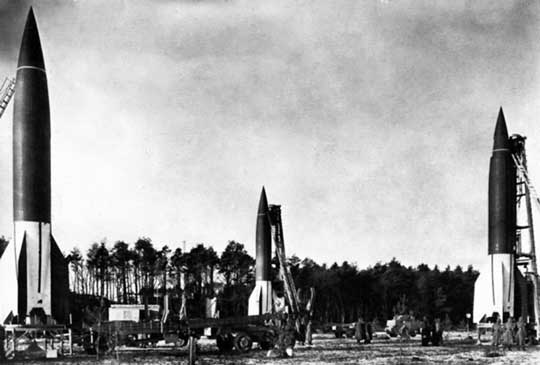

The V-2 was equipped with a liquid-propellant rocket engine, had a speed of 5760 km / h (2880 km / h at the time of impact) and a range of 320 km (take-off weight 12 kg, demolition load 500 kg). ).

Looking for methods to actively combat the V-2, the British tried to interfere with the rocket's radio control signal, not yet suspecting that the rocket was not homing. No radio signals that could be associated with the missiles were found. After the launch of the missile offensive, American B-24 Liberator and B-17 Flying Fortress aircraft equipped with Jostle IV radio signal suppression systems were transported to the continent. However, already in November 1944, it was recognized that this method of fighting missiles was unsuccessful - like the abandoned project of creating a powerful magnetic field on the missile flight path; since it would have required vast amounts of energy to produce it, the whole concept was considered impractical.

The first completely successful test of the German V-2 ballistic missile took place on October 3, 1942 (launch from the launch pad, software, gyroscopic guidance).

The interceptors, which defended well against the V-1, were completely powerless in the case of missiles. The only theoretical chance was an attempt to shoot down the rocket shortly after its launch, when it was just picking up speed. An interception attempt was made, for example, by a Spitfire fighter pilot who spotted a rocket flying into the sky, fired from a launcher somewhere in the Netherlands; V-2 picked up speed and took off. The crew of an American B-24 Liberator bomber returning from a daytime raid on Germany was more fortunate. A group of bombers flying over the Netherlands, at an altitude of 3000 m, met a missile heading towards Great Britain. One of the submachine gunners managed to keep his cool and shot down a bullet.

It was the only such successful attempt.

Anti-missile system concept

Artillerymen also made attempts to fight the V-2. The original plan was presented on August 25, 1944 at a meeting of the Crossbow Committee. It was based on the concept of using radar to determine the flight path of a ballistic missile. After her instructions, anti-aircraft batteries on the trajectory of the missiles were to create an area defense of anti-aircraft missiles. It was estimated that a 40 square kilometer dam would be required to destroy one missile. To do this, you will have to lay off 320 people. rockets. The fragments of the rocket were supposed to damage the frontal armor of the rocket, thereby destroying it. Already at the beginning, skeptics noticed two main problems - the issue of the necessary effectiveness of predicting the trajectory and the problem of penetrating the armor of an intercepted missile. The idea was not supported by the crossbow committee.

However, the study continued. The plan presented in January 1945 assumed the detection of a missile 60-75 seconds before the explosion, which made it possible to calculate the trajectory for no more than 15 seconds and inform the anti-aircraft batteries in a specific area. Air Marshal Roderick Hill supported the idea of starting practical tests, stating that it was they, and not just scientific theories, that led to the rapid development and improvement of technology. In the January assumptions, a low, according to the authors, indicator of the probability of hitting one out of 50 missiles was adopted. The missile defense system was to be based on two modified radars: in Aldeburgh (a city on the coast of England, Suffolk County) and Foreness (a cape on the English coast of Kent, near the mouth of the Thames). Each of them had to follow the rocket. If the signals on both radars were the same, this would mean that the missile had crossed the line connecting both stations.

On October 12, 1944, Hitler ordered V-2 strikes to be concentrated on London and Antwerp, important ports through which supplies would soon be delivered for the Allied forces fighting on the Continent.

The next step was to determine the position of the rocket in space and the future position on the trajectory, which was an easy task only in theory. Even the same missiles with the same technical parameters and launch pad can have different flight characteristics - different trajectory, altitude and speed, and even different angles. For example, the target and range of the missiles could be different, set by the operators by indicating the moment the starting engine was turned off. The interception phase was to create a curtain of debris through which the missile would have to pass if the prediction was correct. The force of the collision of the projectile with the fragments will cause it to explode in the air. Proponents argued that the efficiency of the system would increase over time. It turned out, in particular, that as a result of further modifications to the radar, the positioning error will decrease from 300 m (in the pessimistic version) to only 70 m, which, in their opinion, will reduce the number of anti-aircraft missiles fired by only 150 m to a height of 6100 m The concept was not accepted and was rejected as not worthy of expensive practical tests.

General Frederick Pyle, who was in charge of the defense, did not give up and used the disagreement about the start of operational tests to refine the assumptions. The proposed new way to determine the trajectory was to indicate three points: the launch pad, a place removed from London by about 110 km and by about 95 km. Thanks to this, it should have been possible to determine not only any point of the trajectory, but also the point of impact, which, in turn, could give a chance to make an effective interception attempt (by turning on the anti-aircraft battery stationed closest to the flight path) and warn the civilian population. A specially modified Mark V radar (SCR-584) in Steenbergen, the Netherlands, was responsible for indicating the launch point. Its location allowed the missile to be located within seconds of its launch. After processing the data, they were supposed to go in real time to the missile defense system in London, which was to be divided into sectors with a side of 2,5 kilometers. After identifying the sectors at risk of being hit, the relevant information will be transmitted to the appropriate anti-aircraft batteries, which will be able to start a massive fire in a specific place. Assumptions assumed that the average number of missiles fired would be 200 (from 50 to 500).

Critics emphasized that it was not clear whether the hits would have any effect. According to scientists, an anti-aircraft missile, and even an anti-aircraft missile, was too slow to penetrate the missile's armor and detonate it. The tests were not carried out, and the victory over the V-2 missiles was ensured by bombing raids and the defeat of Germany on land. An even more effective defense than in the case of the V-1 was a massive attack. The air operations carried out since September 1944 can be divided into four main categories:

- Planned attacks against predetermined targets, mainly warehouses and yards;

- Reconnaissance flights over places where the presence of objects and installations associated with the V-2 was suspected;

- Railway junction attack missions - considered the most effective of all air operations against the V-2;

- Night missions to destroy the V-2 depot; important due to the fact that most of the German events were held at night.

As a result of reconnaissance activities, the British managed to obtain information about the methods of transporting the V-2. Rockets were usually transported by special trains, which were large in size. The transport train was usually preceded by a heavily armed escort train. All such columns seen were attacked by tactical aircraft, as were the vehicles, which also contained missile components. This was a more difficult task, because the Germans moved mostly at night, used camouflage and even used the signs of the Red Cross.

After a bloody nine-day battle on November 9, 1944, the Germans capitulated on the island of Walcheren to British and Canadian troops. Thus, the German point of resistance protecting the mouth of the Scheldt was neutralized. However, the shells continued to fall. Two of them collapsed near the headquarters of the Ministry of National Security. Another hit a railway bridge, and another hit London, Islington, killing 31 people and injuring 81. A day later, a V-2 outbreak in Luton resulted in 19 deaths and 196 injuries. In December 1944, it was decided to bomb 18 liquefied oxygen plants. However, since as many as eight of them were in the Netherlands - and in a populated area - only two factories were eventually bombed, which was not enough to frustrate the German effort.

The long-awaited breath of martyr London brought not the success of the allies at the front, but the unexpected counter-offensive of the German troops in the Ardennes. The operation, launched on December 16, 1944, was aimed at cutting the Allied forces and capturing Antwerp. To this end, the Germans halted strategic weapon V attacks on Britain, using its increasingly limited means to hit more tactical targets. Air strikes were concentrated on Belgian cities such as Antwerp, or on the main American army logistics hub of Liege, which since October 20 has been the target of a massive V-1 attack (Operation Ludwig). This forced the strengthening of air defense in the area. In the Netherlands, Maastricht became the target. This gave Londoners the opportunity to have a relatively quiet Christmas. By the end of March 1945, 2248 V-1 flying bombs and 1712 V-2 rockets had been dropped on Antwerp.

The beginning of March was not marked by a breakthrough - the number of attacks grew. The dying Third Reich continued its relentless pursuit, increasing the despair and fear of tortured London. On March 3, 1945, it was decided to launch only a limited air strike. Instead of heavy bombers, medium B-25 Mitchells and light Bostons flew over The Hague with a total load of 69 tons of bombs. The raid did not bring the expected results - it ended only in civilian casualties, which was opposed by the Dutch embassy in London. The anti-aircraft fire was so heavy that the crews dropped their bombs ahead of the target. The small impact of the operation on the scale of the attack on the UK is shown by the numbers. Between 3 and 9 March 1945, 65 rockets were recorded, 60 percent of which fell on London.

The elimination of the threat posed by the V-2 was supposed to occur as a result of the physical capture of all launchers. Before this happened, the Allies continued their air raids in an attempt to eliminate the threat in this way. Bombs fell not only on The Hague, but also on Duindigt, Ockenburg, Ravelin and Rust en Vreigd. Nevertheless, from March 10 to March 16, 1945, 50 rockets were fired, and from March 17 to March 23, 1945, 62 V-2 rockets.

By the end of March 1945, 2248 V-1 missile carriers and 1712 V-2 ballistic missiles had fallen on Antwerp. The photo shows the tragic consequences of the V-2 explosion; Antwerp, 27 November 1944

On March 22, 1945, the 3rd Army of General George Patton crossed the Rhine, and a day later the last rocket hit Antwerp. Four days later, the rocket units were ordered to immediately evacuate deep into Germany. On this day, March 27, 1945, the last V-2 rocket fell on Great Britain (16:45, Orpington, London). The unequal battle finally ended on April 3, 1945, when Marshal Roderick Hill stopped all air operations against targets in the Netherlands, which were supposed to be related to ballistic and jet missiles. On April 13, Home Chain radars stopped waiting for the missiles to arrive. On April 20, restrictions on flights in anti-V-1 air defense combat zones were lifted. London and all of Britain were finally safe.

Landscape after the battle

The months-long "Second Battle of Britain" finally ended with the victory of Great Britain. However, it was an extremely costly battle. The defensive measures (from both V-1 flying bombs and V-2 ballistic missiles) cost more than £48 million. The costs associated with the elimination of the consequences (24 52 buildings destroyed, 250 2 seriously damaged) were incomparably higher. There would certainly have been more victims if not for about a million people leaving London at their own expense, as well as over 2724 thousand. - mostly children - are organized and funded by the authorities. This was a record number, because even four years earlier, during the famous Blitz, fewer people were leaving London. The number of victims is not exactly known and varies depending on the source. For example, Winston Churchill reports that in the UK, V-6476 killed XNUMX people and seriously injured XNUMX people.