British strategic aviation until 1945 part 3

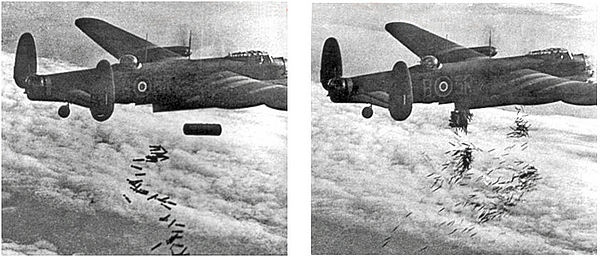

In late 1943, the Halifax (pictured) and Stirling heavy bombers were withdrawn from air raids on Germany due to heavy losses.

Although A. M. Harris, thanks to the support of the Prime Minister, could look to the future with confidence when it came to the expansion of Bomber Command, he certainly could not be so calm when considering his achievements in the field of operational activities. Despite the introduction of the Gee radio navigation system and the tactics of using it, night bombers were still a "fair weather" and "easy target" formation with two or three failures per success.

Moonlight could only be counted on a few days a month and favored more and more efficient night fighters. The weather was a lottery and "easy" goals usually didn't matter. It was necessary to find methods that would help make the bombing more effective. Scientists in the country worked all the time, but it was necessary to wait for the next devices that support navigation. The entire connection was supposed to be equipped with the G system, but the time of its effective service, at least over Germany, was inexorably coming to an end. The solution had to be sought in another direction.

The formation of the Pathfinder Force in March 1942 from her allowances upset a certain balance in bomber aircraft - from now on, some crews had to be better equipped, which allowed them to achieve better results. This certainly spoke in favor of the fact that experienced or simply more capable crews should lead and support a large group of "middle class" men. It was a reasonable and seemingly self-evident approach. It is noted that from the very beginning of the blitz, the Germans did just that, who additionally supplied these crews with navigation aids; the actions of these "guides" increased the effectiveness of the main forces. The British approached this concept differently for several reasons. First, they didn't have any navigation aid before. Moreover, they seem to have been initially discouraged from the idea - in their first "official" retaliatory surface raid on Mannheim in December 1940, they decided to send some experienced crews ahead to start a fire in the city center and target the rest of the forces. The weather conditions and visibility were ideal, but not all of these crews managed to drop their loads in the right area, and the calculations of the main forces were ordered to put out the fires caused by the "gunners" who did not start in the right place and the whole raid was very scattered. The findings of this raid were not encouraging.

In addition, earlier such decisions did not favor the tactics of actions - since the crews were given four hours to complete the raid, fires located in a good place could be extinguished before other calculations appeared over the target to use or strengthen them. . Also, although the Royal Air Force, like all other air forces in the world, were elite in their own way, especially after the Battle of Britain, they were quite egalitarian within their ranks - the system of fighter aces was not cultivated, and there confidence in the idea of "elite squadrons" was not. This would be an attack on the common spirit and destroy the unity by creating individuals from the "chosen ones". Despite this trend, voices were heard from time to time that tactical methods could only be improved by creating a special group of pilots specialized in this task, as Lord Cherwell believed in September 1941.

This seemed like a reasonable approach, since it was obvious that such a squad of experienced aviators, even starting from scratch, would eventually have to achieve something in the end, if only because they would do it all the time and at least know what was done wrong - in such squadrons experience would be accumulated and organic development would pay off. On the other hand, recruiting several different experienced crews from time to time and placing them in the forefront was a waste of the experience they could have gained. This line of opinion came to be strongly supported by the Air Ministry's Deputy Director of Bomber Operations, Captain General Bufton, who was an officer with considerable combat experience from this world war rather than the previous one. As early as March 1942, he suggested to A. M. Harris that six such squadrons be created specifically for the role of "guides". He believed that the task was urgent and therefore 40 of the best crews from the entire Bomber Command should be allocated to these units, which would not be a weakening of the main forces, because each squadron would provide only one crew. G/Cpt Bufton was also openly critical of the organization of the formation for not fostering grassroots initiatives or moving them to an appropriate place where they could be analyzed. He also added that, on his own initiative, he conducted a test among various commanders and staffs and that his idea received strong support.

A. M. Harris, like all his group commanders, was categorically opposed to this idea - he believed that the creation of such an elite corps would have a demoralizing effect on the main forces, and added that he was pleased with the current results. In response, G/Cpt Bufton made many strong arguments that the results were actually disappointing and were the result of a lack of good "aiming" in the first phase of the raids. He added that the constant lack of success is a major demoralizing factor.

Without going into further details of this discussion, it should be noted that A. M. Harris himself, who undoubtedly had an offensive character and a penchant for coloring, did not fully believe in the words addressed to Mr. Captain Bafton. This is evidenced by his various exhortations sent to group commanders for the poor performance of their crews, and his firm position on placing in each aircraft an unfavorably perceived aviation camera among the crews in order to force the pilots to diligently perform their task and once and for all put an end to the "decutors" . A. M. Harris even planned to change the rule for counting combat moves to one in which most sorties would have to be counted on the basis of photographic evidence. The group commanders themselves knew about the problems of formation, which did not disappear as if by magic with the advent of Gee. All this spoke in favor of following the advice and concept of G/kapt Bafton. Opponents of such a decision, led by A. M. Harris, looked for all possible reasons not to create a new formation of "guides", - new ones were added to the old arguments: the proposal of half-measures in the form of establishing the formal function of "air raid gunners", the inadequacy of various machines for such tasks, and, finally, the assertion that the system is unlikely to be more efficient - why would the prospective specialist gunner see him in difficult conditions

more than anyone else?