The US Constitution and Information Processing - The Extraordinary Life of Herman Hollerith

The whole problem began in 1787 in Philadelphia, when rebellious former British colonies tried to create the US Constitution. There were problems with this - some states were larger, others smaller, and it was about establishing reasonable rules for their representation. In July (after several months of wrangling) an agreement was reached, dubbed the "Great Compromise". One of the clauses of this agreement was the provision that every 10 years in all US states a detailed census of the population would be conducted, on the basis of which the number of states' representation in government bodies was to be determined.

At the time, it didn't seem like much of a challenge. The first such census in 1790 numbered 3 citizens, and the census list contained only a few questions - there were no problems with the statistical processing of the results. Calculators dealt with this easily.

It soon became clear that both a good and a bad start. The US population grew rapidly: from census to census by almost 35% exactly. In 1860, more than 31 million citizens were counted - and at the same time the form began to bloat so much that Congress had to specifically limit the number of questions allowed to be asked to 100 in order to ensure that the questionnaire could be processed. arrays of received data. The 1880 census turned out to be as complicated as a nightmare: the bill exceeded 50 million, and it took 7 years to sum up the results. The next list, set for 1890, was already clearly unfeasible under these conditions. The US Constitution, a sacred document for Americans, is under serious threat.

The problem was noticed earlier and even attempts were made to solve it almost as far back as 1870, when a certain Colonel Seaton patented a device that made it possible to slightly speed up the work of calculators by mechanizing a small fragment of it. Despite the very meager effect - Seaton received $ 25 from Congress for his device, which at that time was gigantic.

Nine years after Seaton's invention, he graduated from Columbia University, a young man eager for success, the son of an Austrian immigrant to the United States named Herman Hollerith, born in 1860. he had some impressive income - with the help of various statistical surveys. He then began working at the famed Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a lecturer in mechanical engineering, then took a job at the federal patent office. Here he began to think about improving the work of census takers, to which he was undoubtedly prompted by two circumstances: the size of Seaton's premium and the fact that a competition was announced for the mechanization of the upcoming 1890 census. The winner of this competition could count on a huge fortune.

Zdj. 1 German Hollerit

Hollerith's ideas were fresh and, therefore, hit the proverbial bullseye. First, he decided to start electricity, which no one had thought about before him. The second idea was to get a specially perforated paper tape, which had to be scrolled between the contacts of the machine and thus shortened when it was necessary to send a counting pulse to another device. The last idea at first turned out to be so-so. It was not easy to break through the tape, the tape itself “loved” to tear, did its movement have to be extremely smooth?

The inventor, despite initial setbacks, did not give up. He replaced the ribbon with the thick paper cards that were once used in weaving, and that was the crux of the matter.

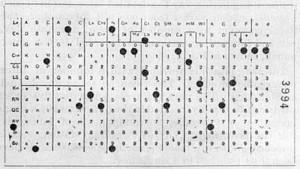

Map of his idea? quite reasonable dimensions of 13,7 by 7,5 cm? originally contained 204 perforation points. Appropriate combinations of these perforations coded responses to questions on the census form; this ensured the correspondence: one card - one census questionnaire. Hollerith also invented—or in fact vastly improved upon—a device for error-free punching of such a card, and very quickly improved the card itself, increasing the number of holes to 240. However, its most important design was electric? • Which processed the information read from the perforation and additionally sorted the skipped cards into packets with common characteristics. Thus, by selecting, for example, those relating to men from all the cards, they could subsequently be sorted according to criteria such as, say, occupation, education, etc.

The invention - the whole complex of machines, later called "calculating and analytical" - was ready in 1884. In order to make them not only on paper, Hollerith borrowed $2500, made a test kit for him, and on September 23 of that year produced a patent application that required him to make a rich man and one of the most famous people in the world. Since 1887, the machines found their first job: they began to be used in the US military medical service to maintain health statistics for US Army personnel. All this together initially brought the inventor a ridiculous income of about $ 1000 a year?

Photo 2 Hollerith punched card

However, the young engineer kept thinking about inventory. True, the calculations of the amount of materials needed were at first glance rather unattractive: more than 450 tons of cards alone would be required for the census.

The competition announced by the Census Bureau was not easy and had a practical stage. Its participants had to process on their devices a huge amount of data already accumulated during the previous census, and prove that they would get consistent results much faster than their predecessors. Two parameters had to be decisive: calculation time and accuracy.

The competition was by no means a formality. William S. Hunt and Charles F. Pidgeon stood next to Hollerith in the deciding game. They both used bizarre subsystems, but the basis for them was hand-crafted counters.

Hollerith's machines literally destroyed the competition. They turned out to be 8-10 times faster and several times more accurate. The Census Bureau ordered the inventor to rent 56 kits from him for a total of $56 a year. It was not yet a gigantic fortune, but the amount allowed Hollerith to work in peace.

The 1890 census arrived. The success of Hollerith's kits was overwhelming: six weeks (!) after the census conducted by almost 50 interviewers, it was already known that 000 citizens lived in the United States. As a result of the collapse of the state, the constitution was saved.

The builder's final earnings after the end of the census amounted to a "considerable" sum of $750. In addition to his fortune, this achievement brought Hollerith great fame, among other things, he dedicated an entire issue to him, heralding the beginning of a new era of computing: the era of electricity. Columbia University considered his machine paper equivalent to his dissertation and awarded him a Ph.D.

Photo 3 Sorter

And then Hollerith, already having interesting foreign orders in his portfolio, founded a small firm called the Tabulating Machine Company (TM Co.); it seems that he even forgot to register it legally, which, however, was not necessary at that time. The company simply had to assemble sets of machines provided by subcontractors and prepare them for sale or rental.

Hollerith's plants were soon in operation in several countries. First of all, in Austria, which saw a compatriot in the inventor and began to produce his devices; except that here, using rather dirty legal loopholes, he was denied a patent, so that his income turned out to be much lower than expected. In 1892 Hollerith's machines carried out a census in Canada, in 1893 a specialized agricultural census in the United States, then they went to Norway, Italy and finally to Russia, where in 1895 they made the first and last census in history under the tsarist government. authorities: the next was made only by the Bolsheviks in 1926.

Photo 4 Hollerith machine set, sorter on the right

The inventor's income grew despite copying and bypassing his patents for power - but so did his expenses, as he gave almost all of his fortune to new production. So he lived very modestly, without pomp. He worked hard and did not care about his health; doctors ordered him to significantly limit his activities. In this situation, he sold the company to TM Co and received $1,2 million for his shares. He was a millionaire and the company merged with four others to become CTR - Hollerith became a board member and technical advisor with a $20 annual fee; He left the board of directors in 000 and left the company five years later. On June 1914, 14, after another five years, his company once again changed its name - to the one by which it is widely known to this day on all continents. Name: International Business Machines. IBM.

In mid-November 1929, Herman Hollerith caught a cold and on November 17, after a heart attack, died at his Washington residence. His death was only briefly mentioned in the press. One of them mixed up the name IBM. Today, after such a mistake, the editor-in-chief would definitely lose his job.