Operation Husky part 1

Landing LCM landing barge bounces off the side of USS Leonard Wood heading for the beaches of Sicily; July 10, 1943

In terms of later battles to which history has given greater prominence, such as Operation Overlord, the Allied landing in Sicily may seem like a minor event. However, in the summer of 1943, no one thought about it. Operation Husky was the first decisive step taken by the Western allies to liberate Europe. Above all, however, it was the first large-scale operation of the combined sea, air and land forces - in practice, a dress rehearsal for the landings in Normandy next year. Weighed down by the bad experience of the North African campaign and the resulting Allied prejudice, it also proved to be one of the greatest tensions in the history of the Anglo-American alliance.

In 1942/1943, Roosevelt and Churchill were under increasing pressure from Stalin. The battle of Stalingrad was just underway, and the Russians demanded that a “second front” be created in Western Europe as soon as possible, which would unload them. Meanwhile, Anglo-American forces were not ready to invade the English Channel, as the landings at Dieppe in August 1942 painfully demonstrated. The only place in Europe where the Western Allies could risk fighting the Germans on land was the southern fringes of the continent. .

"We will become a laughingstock"

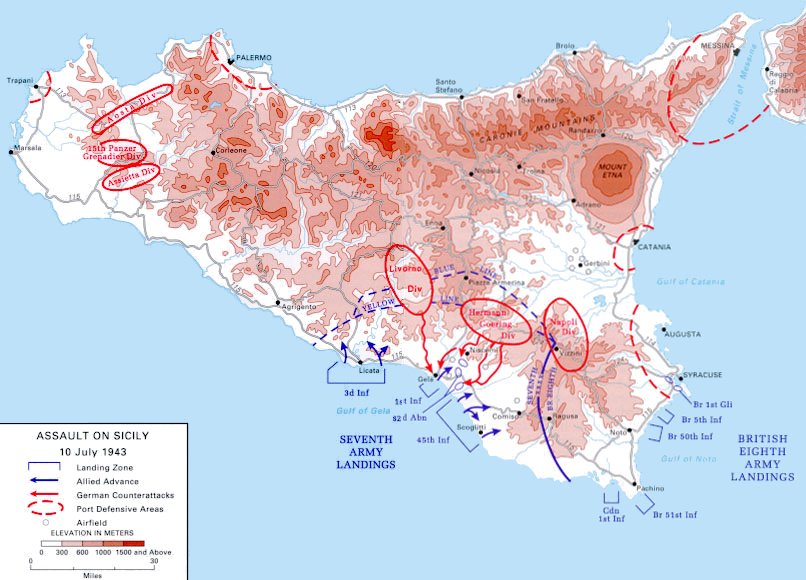

The idea of an amphibious landing in Sicily first arose in London in the summer of 1942, when the War Cabinet's Joint Planning Staff began to consider possible operations by British forces in 1943. Then two strategically important targets were identified in the Mediterranean Sea, Sicily and Sardinia, which received the code names Husky and Sulfur. The much less defended Sardinia could have been captured a few months earlier, but was a less promising target. Although it was suitable for air operations from there, the ground forces could only use it as a commando base for attacks on southern France and mainland Italy. The main disadvantage of Sardinia from a military point of view was the lack of ports and beaches suitable for landings from the sea.

While the British victory at El Alamein and the successful landing of the Allies in Morocco and Algiers (Operation Torch) in November 1942 gave the Allies hope for a speedy end to hostilities in North Africa, Churchill thundered: “We will be a laughing stock if in the spring and in the summer of 1943. it turns out that neither British nor American ground forces are at war anywhere with either Germany or Italy. Therefore, in the end, the choice of Sicily as the goal of the next campaign was determined by political considerations - when planning actions for 1943, Churchill had to take into account the scale of each operation in order to be able to present it to Stalin as a reliable replacement for the invasion of France. So the choice fell on Sicily - although at this stage the prospect of conducting a landing operation there did not arouse enthusiasm.

From a strategic point of view, starting the entire Italian campaign was a mistake, and the landing in Sicily proved to be the beginning of a road to nowhere. The Battle of Monte Cassino proves how difficult and unnecessarily bloody the attack on the narrow, mountainous Apennine Peninsula was. The prospect of overthrowing Mussolini was little consolation, since the Italians, as allies, were more of a burden to the Germans than an asset. Over time, the argument, made a little retroactively, also collapsed - contrary to the hopes of the allies, their subsequent offensives in the Mediterranean Sea did not fetter significant enemy forces and did not provide significant relief to other fronts (eastern, and then western).

The British, though not themselves convinced of the invasion of Sicily, now had to win the idea over to even more skeptical Americans. The reason for this was the conference in Casablanca in January 1943. There, Churchill "sculpted" Roosevelt (Stalin defiantly refused to come) to carry out Operation Husky, if possible, in June - immediately after the expected victory in North Africa. Doubts remain. As Captain Butcher, Eisenhower's naval adjutant: Having taken Sicily, we just gnaw on the sides.

“He should be the commander in chief, not me”

In Casablanca, the British, better prepared for these negotiations, achieved another success at the expense of their ally. Although General Dwight Eisenhower was the commander-in-chief, the rest of the key positions were taken by the British. Eisenhower's deputy and commander-in-chief of the allied army during the campaigns in Tunisia and subsequent campaigns, including in Sicily, was General Harold Alexander. The naval forces were placed under the command of Adm. Andrew Cunningham, Commander of the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean. In turn, responsibility for aviation was assigned to Marshal Arthur Tedder, commander of the Allied Air Force in the Mediterranean.