Fuel Efficiency Ratings | what do they tell you?

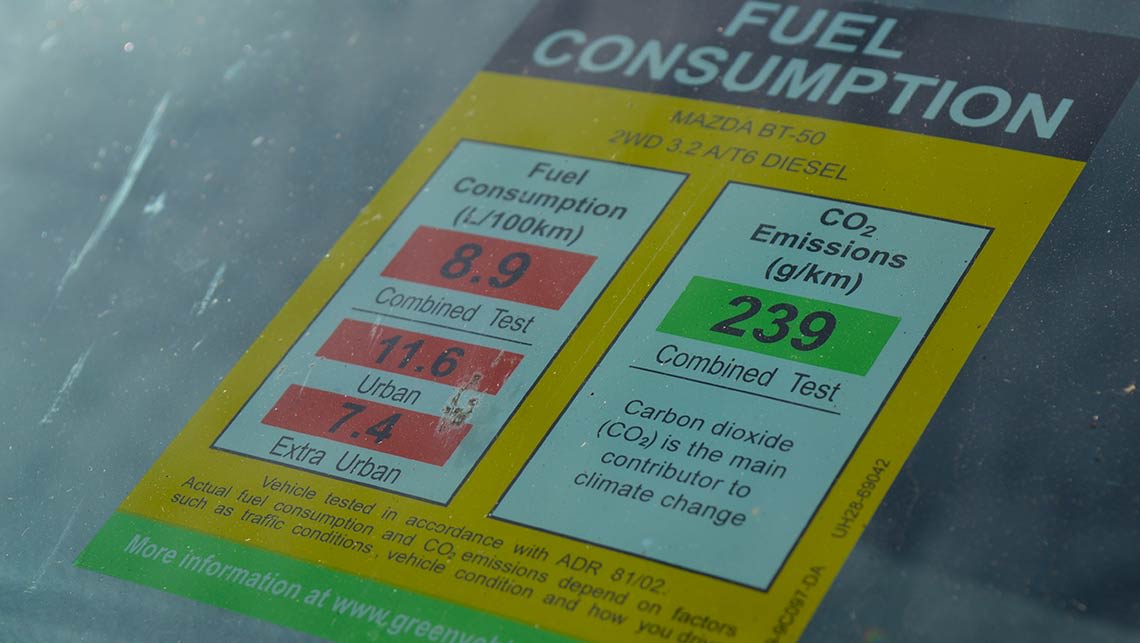

The fuel consumption label, which is required by federal law, must be affixed to the windshield of new vehicles.

What do the fuel consumption numbers on the windshield of new cars mean and where do they come from?

Sounds like one of those desperately boring jobs you're glad someone else is doing there. Of course, to get those official average fuel consumption numbers that we so often hear on new cars, or read on the ADR 81/02 fuel consumption label that federal law requires affixing to the windshield of new cars, there must be a fleet of people moving very slowly. and carefully.

How else do car companies come up with these official fuel consumption figures, telling us about car CO2 emissions and how many liters of gasoline or diesel fuel we will use in various modes - urban, extra-urban ("extra-urban" fuel consumption refers to use? on the highway ) and combined (which finds the average of urban and suburban numbers "city vs. highway")?

You might be surprised to know that these numbers are actually generated by car companies putting their cars on a dynamometer (a kind of rolling road like a treadmill for cars) for 20 minutes and "simulating" driving through an "urban" city. (average speed 19 km/h), on an "extra-urban" motorway (a dashing maximum speed of 120 km/h), with a "combined" fuel economy figure calculated by simply averaging the two results. This could put an end to any mystery surrounding why you can't achieve real life fuel consumption claims.

They are trying to make the test, which is dictated by Australian design rules and based on procedures used by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), as realistic as possible by simulating aerodynamic drag and inertia and using a fan to simulate airflow. over the front of the car, aiming to eventually put accurate fuel efficiency ratings on the Australian fuel consumption label.

As one industry expert explained to us, because everyone has to take the same test, and it's so tightly controlled that no one can spend more money to get a better score, and thus "it allows apples to apples to be compared" .

Even though those apples may not be as juicy when you bring them home. Here is how a typical BMW Australia representative responds to the question that the official figures do not correspond to the real figures: “The combination of high-performance engines and intelligent electronic transmission control allows us to fully comply with regulatory requirements, as well as achieve the best results for our customers.”

Truly, a politician could not have said less and better.

Fortunately, James Tol, certification and regulatory manager for Mitsubishi Australia, was much more outspoken. Mitsubishi, of course, has even more difficulty because it offers plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (or PHEVs) such as the Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV, which claims a combined fuel economy figure of just 1.9 liters per 100 km.

“Obtaining fuel data is time-consuming and costly, and people need to remember that the numbers they achieve in their own cars depend a lot on where and how they drive,” Mr. Told explained.

“They will also be affected by what accessories you may have fitted to your vehicle, how much weight you carry or whether you are towing.

“There has been a lot of debate about the merits of lab fuel consumption tests and how they compare to real driving. Improvements have been made to laboratory tests in Europe, which aim to more accurately represent real world conditions. These new procedures have not yet been adopted into Australian law.

“However, by necessity, this remains a laboratory test, and people may or may not achieve the same results when driving in the real world.”

As he notes, laboratory tests guarantee reproducibility of results and a level playing field for comparing different brands and models. These are comparative, not definitive instruments.

“PHEVs are sometimes reported to have significant deviations when used in the 'real world'. My guess is that PHEVs are an easy headline target in this regard in the current test. It comes down to the fact that the figure claimed is a comparative tool based on a prescribed route of travel with a certain length and a set of variations, and not a final result based on real experience,” adds Mr. Tol.

“During weekly commutes with regular charging, depending on the distance to work and your driving style, it is quite possible to not use fuel at all.

“During a longer trip, or if the battery has not been recharged, the fuel economy of a PHEV will be more similar to that of a conventional (non-plug-in) hybrid. This performance range is not covered by one declared figure, which must be specified in accordance with the regulations.

“However, as a comparison tool, the reported figure can certainly provide insight into comparative performance with other PHEVs.”