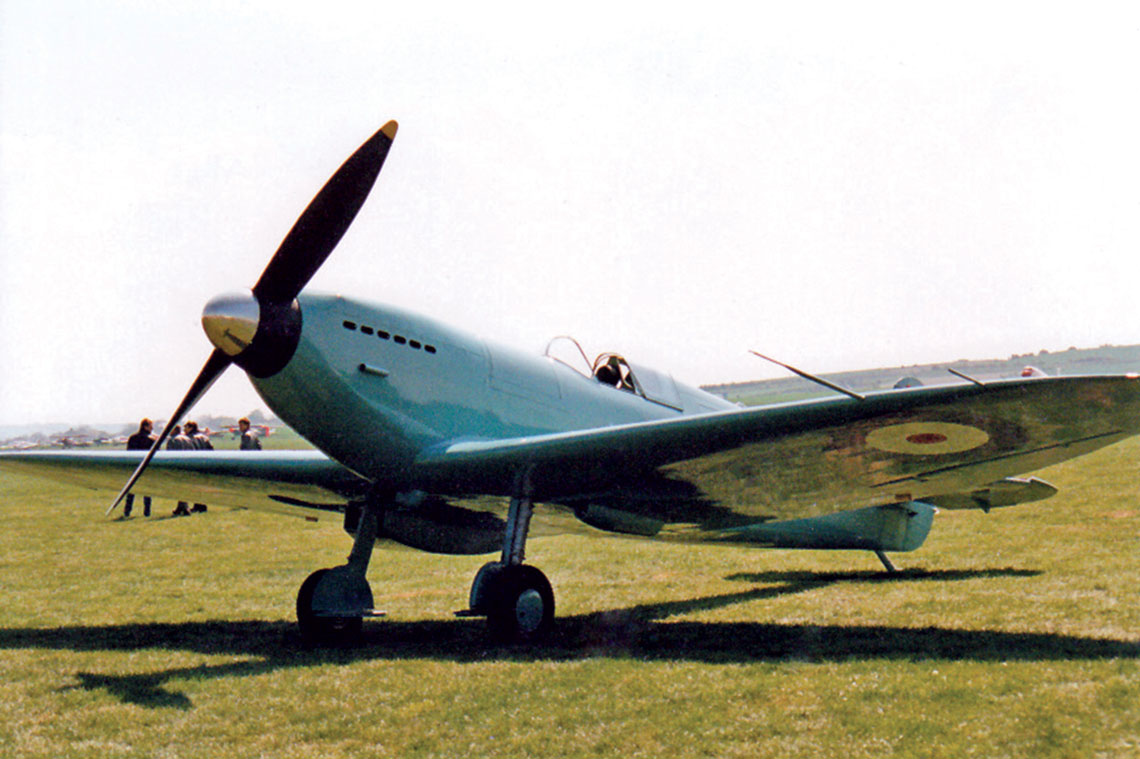

Supermarine Spitfire The legendary RAF fighter.

Modern replica of the first Supermarine 300 fighter prototype, also called F.37/34 or F.10/35 to Air Ministry specification, or K5054 to RAF registration number.

The Supermarine Spitfire is one of the most famous aircraft of the Second World War, serving from the very beginning to the last day of the conflict, still being one of the main types of RAF fighter aircraft. Eight of the fifteen squadrons of the Polish Air Force in the UK also flew Spitfires, so it was the most numerous type in our aviation. What is the secret of this success? How did the Spitfire differ from other aircraft designs? Or maybe it was an accident?

The Royal Air Force (RAF) in the 30s and the first half of the 1930s was strongly influenced by Gulio Due's theory of destroying the enemy with massive air strikes. The main proponent of the offensive use of aviation to destroy the enemy by aerial bombardment was the first Chief of Staff of the Royal Air Force, General Hugh Montagu Trenchard, later Viscount and Chief of the London Police. Trenchard served until January 1933, when he was replaced by General John Maitland Salmond, who held identical views. He was succeeded in May XNUMX by General Edward Leonard Ellington, whose views on the use of the Royal Air Force were no different from those of his predecessors. It was he who opted for the expansion of the RAF from five bomber squadrons to two fighter squadrons. The "air combat" concept was a series of strikes against enemy airfields designed to reduce enemy aircraft on the ground when it was known what their homing was. Fighters, on the other hand, had to look for them in the air, which sometimes, especially at night, was like looking for a needle in a haystack. At that time, no one foresaw the advent of radar, which would completely change this situation.

In the first half of the 30s, there were two categories of fighters in the UK: area fighters and interceptor fighters. The former were to be responsible for the air defense of a specific area day and night, and visual observation posts located on British territory were to be aimed at them. Therefore, these aircraft were equipped with radios and, in addition, had a landing speed limit to ensure safe operation at night.

On the other hand, the fighter-interceptor had to operate on close approaches to the coast, aim at air targets according to the indications of listening devices, then independently detect these targets. It is known that this was possible only during the day. There were also no requirements for the installation of a radio station, since there were no observation posts at sea. The fighter-interceptor did not need a long range, the detection range of enemy aircraft using listening devices did not exceed 50 km. Instead, they needed high rate of climb and maximum rate of climb to be able to attack enemy bombers even before the shore from which the zone fighters were launched, usually behind the screen of anti-aircraft fire deployed on the shore.

In the 30s, the Bristol Bulldog fighter was considered as an area fighter, and the Hawker Fury was considered as an interceptor fighter. Most writers on British aviation do not distinguish between these classes of fighters, giving the impression that the United Kingdom, for some unknown reason, operated several types of fighters in parallel.

We have written about these doctrinal nuances many times, so we decided to tell the story of the Supermarine Spitfire fighter from a slightly different angle, starting with the people who made the greatest contribution to the creation of this extraordinary aircraft.

Perfectionist Henry Royce

One of the main sources of the success of the Spitfire was its power plant, the no less legendary Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, created at the initiative of such an outstanding person as Sir Henry Royce, who, however, did not wait for the success of his “child”.

Frederick Henry Royce was born in 1863 in a typical English village near Peterborough, about 150 km north of London. His father ran a mill, but when he went bankrupt, the family moved to London for bread. Here, in 1872, the father of F. Henry Royce died, and after only one year of schooling, 9-year-old Henry had to earn his living. He sold newspapers on the street and delivered telegrams for a meager fee. In 1878, when he was 15, his status improved as he worked as an apprentice in the workshops of the Great Northern Railway at Peterborough and, thanks to his aunt's financial assistance, returned to school for two years. Work in these workshops gave him knowledge of mechanics, which interested him very much. Mechanical engineering became his passion. After completing his studies, he began working at a tool factory in Leeds before returning to London where he joined the Electric Light and Power Company.

In 1884, he persuaded his friend to jointly open a workshop for installing electric light in apartments, although he himself had only 20 pounds to invest (at that time it was quite a lot). The workshop, registered as FH Royce & Company in Manchester, began to develop very well. The workshop soon began producing bicycle dynamos and other electrical components. In 1899, no longer a workshop, but a small factory was opened in Manchester, registered as Royce Ltd. It also produced electric cranes and other electrical equipment. However, increased competition from foreign companies prompted Henry Royce to switch from the electrical industry to the mechanical industry, which he knew better. It was the turn of motors and cars, about which people began to think more and more seriously.

In 1902, Henry Royce bought a small French car Decauville for personal use, equipped with a 2 hp 10-cylinder internal combustion engine. Of course, Royce had a lot of comments on this car, so he dismantled it, carefully examined it, redid it and replaced it with several new ones in accordance with his idea. Starting in 1903, in a corner of the factory floor, he and two assistants built two identical machines assembled from recycled parts from Royce. One of them was transferred to Royce's partner and co-owner Ernest Claremont, and the other was bought by one of the directors of the company, Henry Edmunds. He was very pleased with the car and decided to meet Henry Royce along with his friend, racing driver, car dealer and aviation enthusiast Charles Rolls. The meeting took place in May 1904, and in December an agreement was signed under which Charles Rolls was to sell cars built by Henry Royce, on the condition that they be called Rolls-Royce.

In March 1906, Rolls-Royce Limited (independent of the original Royce and Company businesses) was founded, for which a new factory was built at Derby, in the center of England. In 1908, a new, much larger Rolls-Royce 40/50 model appeared, which was called the Silver Ghost. It was a great success for the company, and the machine, perfectly polished by Henry Royce, sold well despite its high price.

Aviation enthusiast Charles Rolls several times insisted that the company go into the production of aircraft and aircraft engines, but perfectionist Henry Royce did not want to be distracted and focused on automobile engines and vehicles built on their basis. The case was closed when Charles Rolls died on July 12, 1910 at the age of only 32. He was the first Briton to die in a plane crash. Despite his death, the company retained the Rolls-Royce name.

When World War I broke out in 1914, the government ordered Henry Royce to begin manufacturing aircraft engines. The State Royal Aircraft Factory ordered a 200 hp in-line engine from the company. In response, Henry Royce developed the Eagle engine, which used twelve (V instead of in-line) instead of six cylinders, using solutions from the Silver Ghost automobile engine. The resulting power unit from the very beginning developed 225 hp, exceeding the requirements, and after increasing the engine speed from 1600 to 2000 rpm, the engine finally produced 300 hp. The production of this power unit began in the second half of 1915, at a time when the power of most aircraft engines did not even reach 100 hp! Immediately after this, a smaller version for fighters appeared, known as the Falcon, which developed 14 hp. with a power of 190 liters. These engines were used as the power plant of the famous Bristol F2B fighter. On the basis of this power unit, a 6-cylinder in-line 7-liter engine with a capacity of 105 hp was created. — Hawk. In 1918, an enlarged, 35-liter version of the Eagle was created, reaching an unprecedented power of 675 hp at that time. Rolls-Royce found itself in the field of aircraft engines.

During the interwar period, Rolls-Royce, in addition to making cars, remained in the automobile business. Henry Royce not only created perfect solutions for internal combustion engines himself, but also brought up talented like-minded designers. One of these was Ernest W. Hives, who, under the guidance and close supervision of Henry Royce, designed the Eagle engines and derivatives up to the R family, the other was A. Cyril Lawsey, chief designer of the famous Merlin. He also succeeded in bringing in engineer Arthur J. Rowledge, chief engine engineer for the Napier Lion. The die-cast aluminum cylinder block specialist fell out with Napier management and moved to Rolls-Royce in the 20s, where he played a key role in the development of the company's flagship engine of the 20s and 30s, the 12-cylinder V-twin engine. Kestrel. engine. It was the first Rolls-Royce engine to use an aluminum block common to six cylinders in a row. Later, he also made a significant contribution to the development of the Merlin family.

The Kestrel was an exceptionally successful engine - a 12-cylinder 60-degree V-twin engine with an aluminum cylinder block, a displacement of 21,5 liters and a mass of 435 kg, with a power of 700 hp. in modified versions. The Kestrel was supercharged with a single-stage, single-speed compressor, and in addition, its cooling system was pressurized to increase efficiency, so that water at temperatures up to 150 ° C did not turn into steam. On its basis, an enlarged version of the Buzzard was created, with a volume of 36,7 liters and a mass of 520 kg, which developed a power of 800 hp. This engine was less successful and relatively few were produced. However, on the basis of the Buzzard, R-type engines were developed, designed for racing aircraft (R for Race). For this reason, these were very specific powertrains with high revs, high compression and high, "rotational" performance, but at the expense of durability.