Triple V, a winding road to the submarines of the US Navy

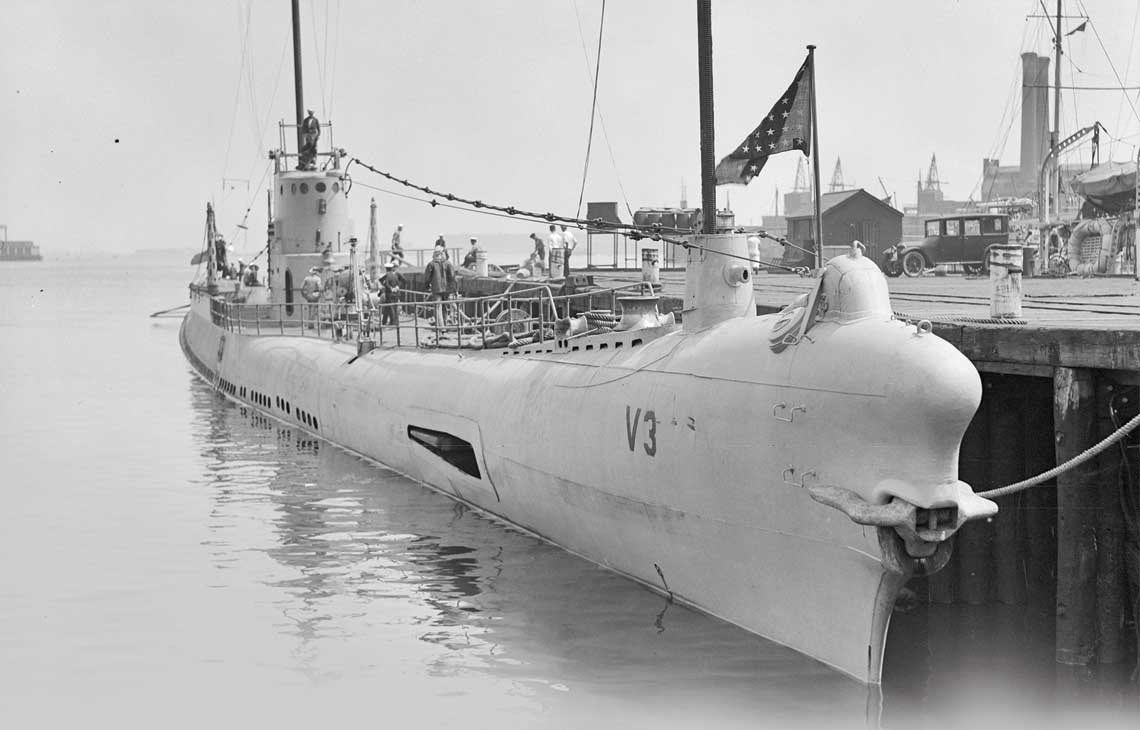

Bonita at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston in 1927 It can be seen that at least part of the light body is welded. Photo Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

Just ten years after the USS Holland (SS 1), the first U.S. Navy submarine, was flag-hoisted, a bold concept for submarines that could work closely with the navy emerged in naval circles. Compared to the small coastal defense ships under construction at that time, these intended fleet submarines would necessarily have to be much larger, better armed, have a greater range and, above all, reach speeds of over 21 knots in order to be able to maneuver freely in teams. with battleships and cruisers.

In total, 6 ships were built according to this concept in the USA. Attempts were made to quickly forget about the first three T-type units, which were built to pre-World War I standards. On the other hand, the next three V-1, V-2 and V-3 ships of interest to us, despite numerous shortcomings, turned out to be one of the milestones in the development of American underwater weapons.

Difficult start

The first sketches of the fleet's submarines were made in January 1912. They depicted ships with a surface displacement of about 1000 tons, armed with 4 bow torpedo tubes and having a range of 5000 nautical miles. More importantly, the maximum speed, both surfaced and submerged, was to be 21 knots! This was, of course, unrealistic at the technical level of the time, but the fleet's vision of fast and heavily armed submarines was so popular that in the fall of that year they were included in the annual tactical games at the Naval War College in Newport. (Rhode Island). The lessons learned from the teachings are encouraging. It was emphasized that the proposed submarines, with the help of minefields and torpedoes, would be able to weaken the enemy's forces before the battle. The threat from under the water forced the commanders to act more carefully, incl. an increase in the distance between ships, which, in turn, made it difficult to concentrate the fire of several units on one target. It was also noted that the collection of even one torpedo that hit the line with a battleship reduced the maneuverability of the entire team, which could outweigh the tide. Interestingly, the thesis was also put forward that submarines would be able to neutralize the advantages of battlecruisers during a sea battle.

After all, new weapons enthusiasts postulated that fast submarines could successfully take over the reconnaissance duties of the main forces, previously reserved for light cruisers (scouts), which the US Navy was like medicine.

The results of the "paper maneuvers" prompted the US Navy General Board to commission further work on the fleet's submarine concept. As a result of the research, the shape of the future ideal ship with a surface displacement of about 1000 tf, armed with 4 launchers and 8 torpedoes, and a cruising range of 2000 nm at a speed of 14 knots crystallized. should have been 20, 25 or even 30 inches! These ambitious goals - especially the last one, achieved only 50 years later - were met with a fair amount of skepticism from the very beginning by the Navy engineering bureau, especially since the internal combustion engines available were capable of reaching 16 centimeters or less.

As the future of the fleet-wide submarine concept hangs in the balance, help has come from the private sector. In the summer of 1913, Lawrence Y. Speer (1870–1950), master builder of the Electric Boat Company shipyard in Groton, Connecticut, submitted two draft designs. These were large units, displacing twice as much as previous U.S. Navy submarines and twice as expensive. Despite many doubts about the design decisions made by Spear and the overall risk of the entire project, the 20 knot speed guaranteed by the Electric Boat on the surface "sold the project". In 1915, the construction of the prototype was approved by Congress, and a year later in honor of the hero of the Spanish-American war, Winfield Scott Schley (later the name was changed to AA-52, and then to T-1). In 1 year, construction began on two twin units, originally designated AA-1917 (SS 2) and AA-60 (SS 3), later renamed T-61 and T-2.

It is worth saying a few words about the design of these three ships, which in later years were called T-shaped, because these forgotten ships were a typical example of ambition, not capability. A fusiform hull design with a length of 82 m and a width of 7 m with a displacement of 1106 tons on the surface and 1487 tons on the draft. In the bow there were 4 torpedo tubes of 450 mm caliber, 4 more were placed amidships on 2 rotating bases. Artillery armament included two 2mm L/76 cannons on turrets hidden below deck. The hard case was divided into 23 compartments. A huge gym occupied the lion's share of its volume. High performance on the surface was to be provided by a twin-screw system, where each drive shaft was rotated directly by two 5-cylinder diesel engines (in tandem) with a power of 6 hp each. each. Expectations for speed and range under water were lower. Two electric motors with a total capacity of 1000 hp powered by electricity from 1350 cells grouped into two batteries. This made it possible to develop a short-term underwater speed of up to 120 knots. The batteries were charged using an additional diesel generator.